Painting

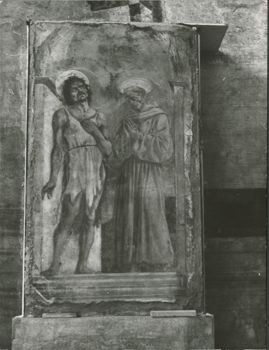

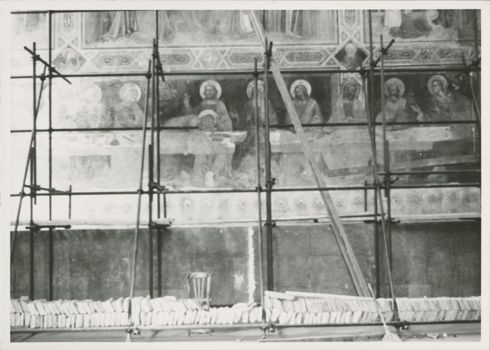

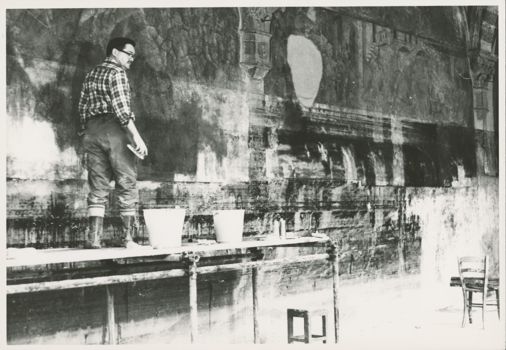

“The damage to frescoes in the city’s many churches was extensive, although the very greatest were fortunately spared. The water just reached the lowest level of the Giottos in the Bardi and Peruzzi chapels in Santa Croce. This meant that the frescoes and fragments of frescoes in the refectory of SantaCroce were almost totally submerged. The lower part of the Taddeo Gaddi “Last Supper” was covered with a thick layer of oil. Serious damage was also sustained at Santa Maria Novellain the Spanish Chapel. Here the water reached the lower part of the frescoes, and in the adjoining Chiostro Verdeand Chiostro dei Morti the frescoes were badly stained with oil. Damage was also done in Ognissanti. In the Santissima Annunziata, especially in the cloister where the chapel of St. Luke with frescoes by Bronzino, Pontormo and Santi di Tito were submerged. Also, the Poccetti Chapel in the church of Santa Maria Maddalena dei Pazzi was half submerged and immediately began to develop the telltale symptoms of mold which has been one of the most preoccupying problems of the restorers.”

Myron P. Gilmore, "Progress of Restoration in Florence,"

Renaissance Quarterly, 20 (1967), pp. 96-97.

“The first large grant by CRIA, made on November 30, 1966, enabled the restorers immediately to begin the care of the soaked frescoes and the removal of the naphtha from their surface. In the first weeks after the flood the restorers had to contend with mold, which quickly looses paint from the intonaco.”

Bates Lowry, CRIA - 6-month report: Frescoes, (Florence) p. (1)

“The tavole, the panel pictures painted on wood, presented a very special problem. They had been submerged in the water for varying lengths of time, and no serious work of restoration could begin until the wood had dried out. The pigment was contained by the application of rice paper to the surface.”

Myron P. Gilmore, "Progress of Restoration in Florence,"

Renaissance Quarterly, 20 (1967), p. 97.

“The State provided the laboratories for the panels, first the Medici Limonaia converted into a crowded hospital with controlled humidity and then the enormous Fortezza da Basso, where a group of eighty restorers and assistant could work.”

Millard Meiss, "Florence and Venice a Year Later,"

Renaissance Quarterly, 21 (1968), p. 105.